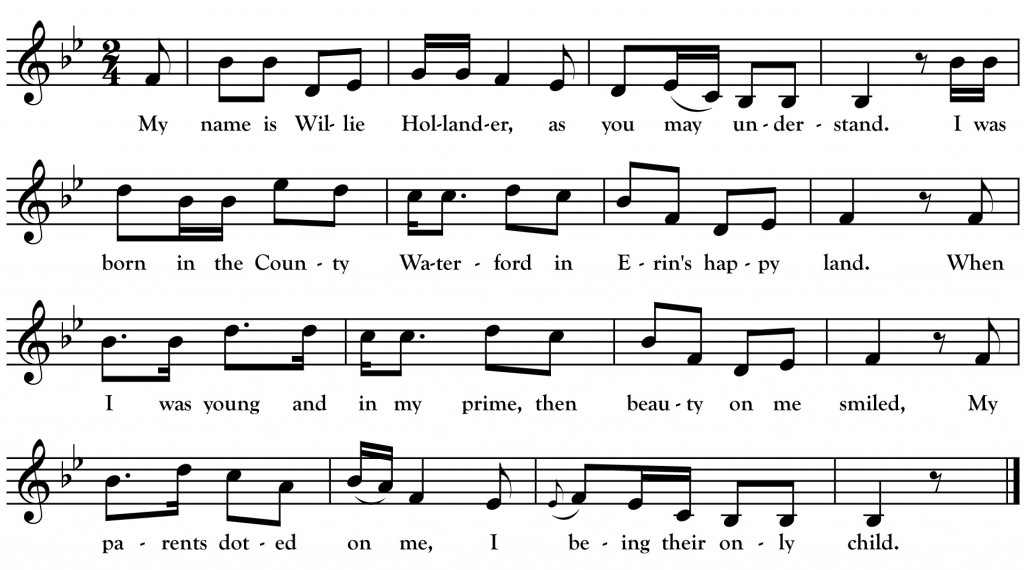

The Flying Cloud (Laws K28)

From the singing of Michael Cassius Dean of Virginia, Minnesota.

Transcribed by Franz Rickaby about 1923.

My name is Willie Hollander, as you may understand,

I was born in the County Waterford in Erin’s happy land;

When I was young and in my prime, then beauty on me smiled,

My parents doted on me, I being their only child.

My father bound me to a trade in Waterford’s fair town,

He bound me to a cooper there by the name of Willie Brown;

I served my master faithfully for eighteen months or more,

Then I shipped on board of the Ocean Queen, bound for Bellefresier’s shore.

And when we reached Bellefreiser’s shore I met with Captain Moore,

The captain of the Flying Cloud, that sails from Baltimore;

He asked me if I would sail with him on a slaving voyage to go,

To the burning shores of Africa where the coffee seeds do grow.

The Flying Cloud was a clipper ship of five hundred tons or more,

She could easy sail ’round anything going out of Baltimore.

Her sails were as white as the driven snow and on them there’s no speck,

And forty-nine brass pounder guns she carried on her deck.

The Flying Cloud was as fine a ship as ever sailed the seas,

Or ever spread a main topsail before a freshening breeze;

I have oft times seen that gallant bark with the wind abaft her beam,

With her main top Royal and stun sails set taking sixteen from the reel.

The first place that we landed ’twas on the African shore,

And five hundred of those poor slaves from their native land we bore;

We marched them out upon our plank and stowed them down below,

It was eighteen inches to the man was all that there was to go.

Early next morning we set sail with our cargo of slaves,

It would have been better for those poor souls if they’d been in their graves;

For the plague and fever came on board, swept half their number away,

And we dragged their bodies on the deck and threw them in the sea.

In the course of three weeks after we arrived on Cuba’s shore,

We sold them to the planters there, to be slaves for evermore;

The rice and coffee seeds to sow beneath the burning sun,

To lead a hard and wretched life until their career was run.

And now our money is all spent and we are off to sea again,

When Captain Moore he came on board and said to us his men:

“There is gold and silver to be had if with me you’ll remain,

We’ll hoist aloft a pirate flag and scour the Spanish Main.”

We all agreed but five young lads who told us them to land,

Two of those were Boston boys, two more from Newfoundland;

And the other was an Irish lad belonging to Trimore,

I wish to God I had joined those boys and went with them on shore.

We sank and plundered many a ship down on the Spanish Main,

Left many a widow and orphan child in sorrow to remain;

We made them walk out on our plank, gave to them a watery grave,

For a saying of our captain was that a dead man tells no tales.

Pursued we were by many ships, both frigates and liners, too,

But for to catch the Flying Cloud was a thing they ne’er could do;

It was all in vain astern of us their cannons roared so loud,

It was all in vain to ever try for to catch the Flying Cloud.

Till a Spanish ship, a man-of-war, the Dungeon, hove in view,

And fired a shot across our bows as a signal to heave to;

We gave to her no answer, but sailed before the wind,

Until a chain shot broke our mizzen mast and then we fell behind.

We cleared our deck for action as she came up ’longside,

And soon from off our quarter decks there ran a crimson tide;

We fought till Captain Moore was killed, and eighty of his men,

When a bomb shell set our ship on fire, we were forced to surrender then.

Now fare you well, you shady groves and the girl that I do adore,

Your voice like music soft and sweet will never cheer me more;

No more will I kiss those ruby lips or clasp that silk-soft hand,

For here I must die a shameful death out in some foreign land.

It was next to New Gate I was brought, bound down in iron chains,

For the plundering of ships at sea down on the Spanish Main;

It was drinking and bad company that made a wretch of me,

So youths beware of my sad fate and my curse on Piracy.

____________________________________________________

“The Flying Cloud” lent its title to and was the first song printed in Michael Cassius Dean’s 1922 songster. It was also the longest song in Dean’s book at 16 stanzas and nearly 800 words. The song is a lament of an Irish lad from County Waterford who joined the crew of a ship bent on slaving and piracy and who is now in London’s Newgate prison facing the hangman’s noose.

Dean may have chosen the song’s name for his book due to its high status as one of the “big” songs known in American lumber camps. Franz Rickaby wrote: “This is the ballad of which it was said that, in order to get a job in the Michigan camps, one had to be able to sing it through from end to end!”

Indeed, Dean himself reported learning his version from singer Jack Troy “in the woods of Lower Michigan” around 1883. Rickaby collected the song from Dean and from North Dakotan farmer Arthur Milloy who himself had come to work in the Michigan lumber woods from Peterborough, Ontario in 1885. A third version was picked up near Fremont, Michigan by Franklin Covell who grew up there in the same era that Dean and Milloy worked in the area. Covell carried the song to Minnesota where he was head keeper of the Split Rock Lighthouse from 1928 to 1944.[i]

There are a number of audio recordings of other variants of “The Flying Cloud” including one from “Yankee” John Galusha who was born around the same time as Dean on the opposite side of the Adirondacks from Dean’s birthplace. Sidney Robertson-Cowell recorded another version from Robert Walker in Crandon, Wisconsin. The airs used by Milloy, Galusha and Walker are all closely related to Dean’s. A very different and quite hauntingly beautiful air was recorded by MacEdward Leach in Newfoundland from singer John Molloy is worth listening to for anyone intrigued by this song.

____________________________________________________

More detailed information on this song from the Traditional Ballad Index

[i] Covell’s version, supplemented by another Minnesotan singer Ole Fonstad, was published in 1922 (the same year as Dean’s songster) in The Journal of American Folk-Lore, XXXV, 370-372 and reprinted in 1924 by Roland Palmer Gray in “Songs and Ballads of the Maine Lumberjacks.”