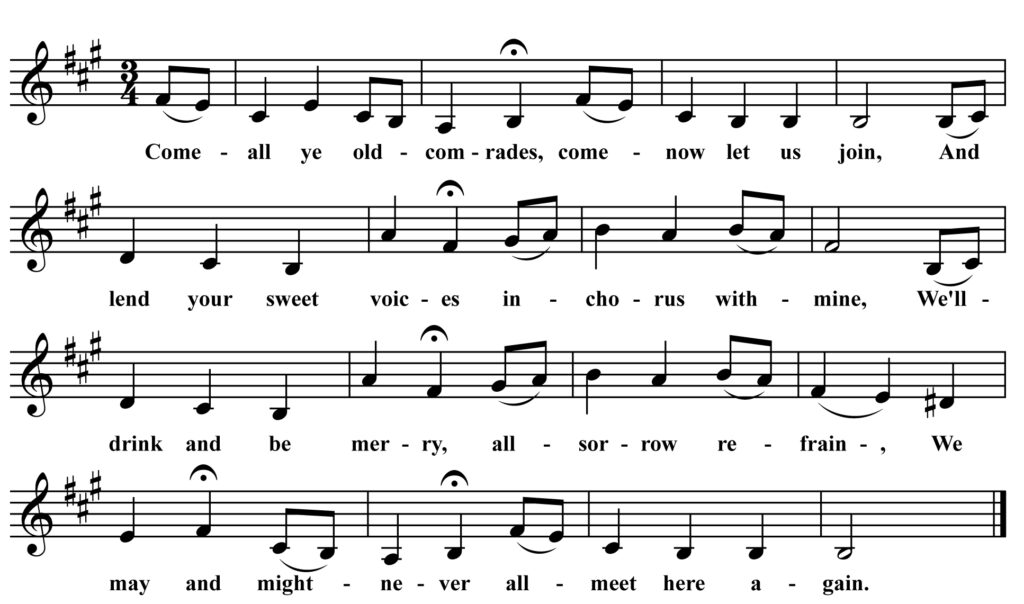

Come All Ye Old Comrades

Come all ye old comrades, come now let us join,

And lend your sweet voices in chorus with mine,

We’ll drink and be merry, all sorrow refrain,

We may and may never all meet here again.

The time is fast approaching when I must away,

To leave my own country for many a long day,

To leave my old comrades so kind and so dear,

I to the Indies my course I must steer.

Fare thee well, I have a mother by the great powers above,

May she always be honored, respected and loved,

I will always respect her by land or by sea,

I’ll ever remember her kindness to me.

Fare thee well, I have a sweetheart whom I dearly love well,

There are none in this country who can her excel,

She smiles at my folly and she sits on my knee,

There’s few in this wide world as happy as we.

Adieu my old comrades, adieu and farewell,

Whether we’ll ever meet again there is no tongue can tell,

We will trust to his mercy who can sink or can save,

To bring me safe over yon proud stormy wave.

We have another song recorded in the Canadian Maritimes by Helen Creighton this month. Many readers will be familiar with Irish or Scottish versions of “Here’s a Health to the Company” aka “Kind Friends and Companions.” It is a well-loved song to close out a night of singing, complete with sing-along chorus.

The above variant, which has no chorus, comes from the singing of Catherine Marion Scott Gallagher (Mrs. Edward Gallagher in Creighton’s notes) who lived at the Chebucto Head lighthouse south east of Halifax, Nova Scotia and was recorded by Creighton in 1949. You can hear Gallagher sing “Come All Ye Old Comrades” on the Nova Scotia Archives website.

Creighton printed another Nova Scotia variant of the song in the book Songs and Ballads from Nova Scotia but, as far as I can tell, the beautiful Gallagher version was not published until the release of this online archive. Gallagher’s phrasing on the recording is really nice and worth a listen for anyone interested in learning this one. The text and melody are also fairly unique from Irish/Scottish versions I am aware of. A great North American version of a favorite song!

.