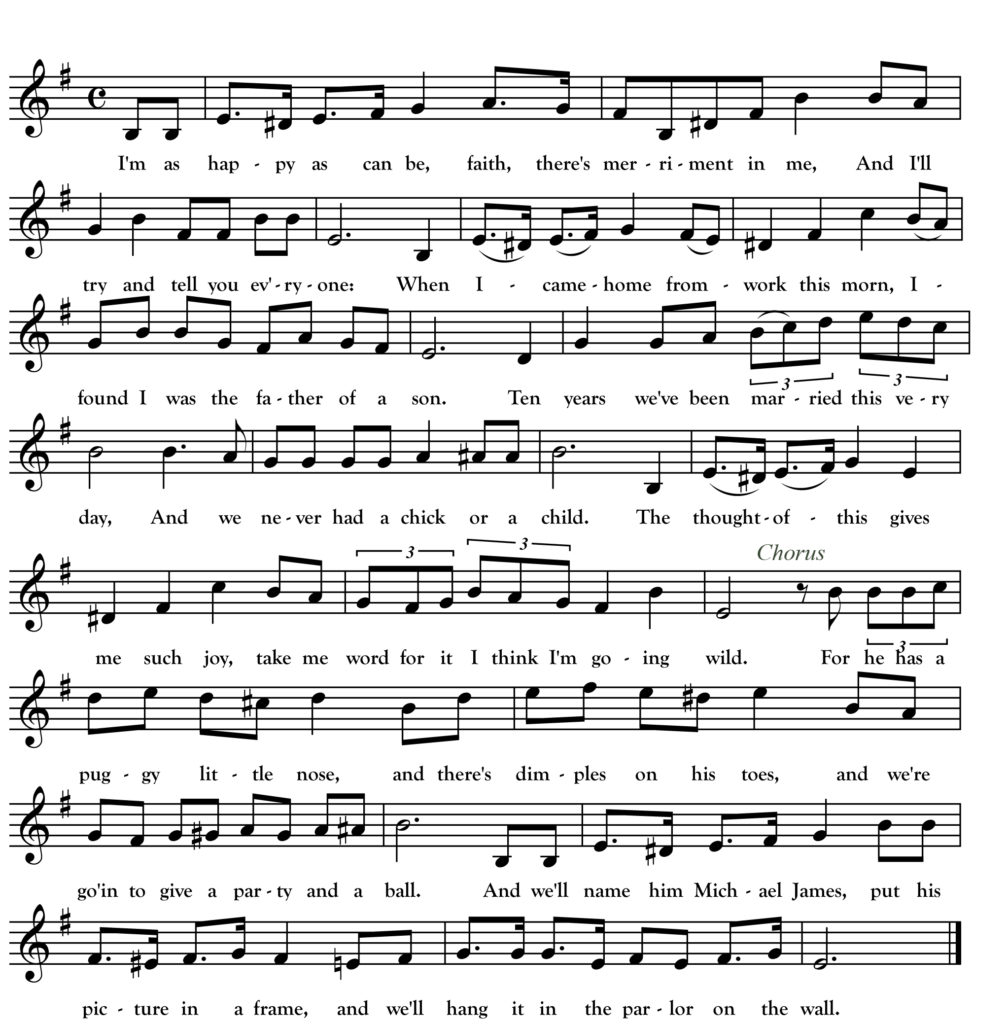

Michael James

I’m as happy as can be, faith, there is merriment in me,

And I’ll try and tell you everyone,

When I came home from work this morn,

I found I was the father of a son.

Ten years we’ve been married this very day,

And we never had a chick or a child,

The thought of this gives me such joy,

Take me word for it, I think I’m going wild.

Chorus—

For he has a puggy little nose, and there’s dimples in his toes,

And we’re going to give a party and a ball,

And we’ll name him Michael James, put his picture in a frame,

And we’ll hang it in the parlor on the wall.

When a man he grows you’ll see, a president he’ll be,

I would never let him run for Alderman,

I’ll buy a horse and dray, and we’ll drive it every day,

You would never find his equal in the land.

He’ll not be a fool, for we’ll send him off to school,

Where they’ll teach him how to row and play ball,

And when he gets some money, we’ll have his picture taken,

And we’ll hang it in the parlor on the wall.

As I have discussed in this column before, logging era singers like Minnesotan Mike Dean typically sang recently composed songs from the American stage alongside older ballads from communities on both sides of the Atlantic. Dean’s repertoire, based on his own self-published songster, seems to have been about half and half. His stage songs are mainly on Irish-American themes common in the late 1800s including: nostalgia for Ireland, stereotypes of urban Irish American life and songs of Irish laborers.

Another category could be “the Irish in American politics.” Three of Dean’s stage songs reference the pursuit of public office and a fourth, “Muldoon, the Solid Man” has its protagonist “called upon to address the meeting” where he “read the Constitution with elocution.” During Dean’s lifetime (1858-1931) Irish-Americans did find success in American politics. Dean lived in Hinckley, Minnesota where Kilkenny native and fellow saloon owner James J. Brennan was the first town president when it was incorporated in 1885. James’ brother Thomas owned the lumber mill in Hinckley and was himself an alderman in St. Paul.

The story behind the song “Michael James” has eluded me for a long time but I recently found the song in an 1881 songster (complete with musical transcriptions!) of compositions by Charles R. Dockstader (1847-1907). Dockstader tried his hand at recycling all the popular song motifs of his day including many riffs on the stage Irishman character. He wrote another song that Dean sang and called “I Left Ireland and Mother Because We Were Poor.”

Dean’s “Michael James” was titled “In the Parlor on the Wall” by Dockstader and was sung on stage by R. M. Carroll, “The Champion Irish Singing Humorist” Harry Kernell and John Sheehan. It appears in the Dockstader Songster published by Philadelphia publisher and music instrument dealer J.W. Pepper in 1881.

The song turns out to have a fine example of the dynamic sort of melody that energized music hall audiences. It also paints a reasonably dignified picture (for its time) of the immigrant father exuberantly pouring his aspirations into his newborn son. I found a March 15, 1902 piece in the The Intermountain Catholic newspaper in Utah about an Ancient Order of Hibernians event in Park City where the chairman of the evening sang the song to an approving crowd. Interestingly, the newspaper wrote: “The programme was appropriate to the occasion and of a nature to please the most critical, while mainly Irish in character there was nothing of the boisterous stage Irishman kind to be seen.”