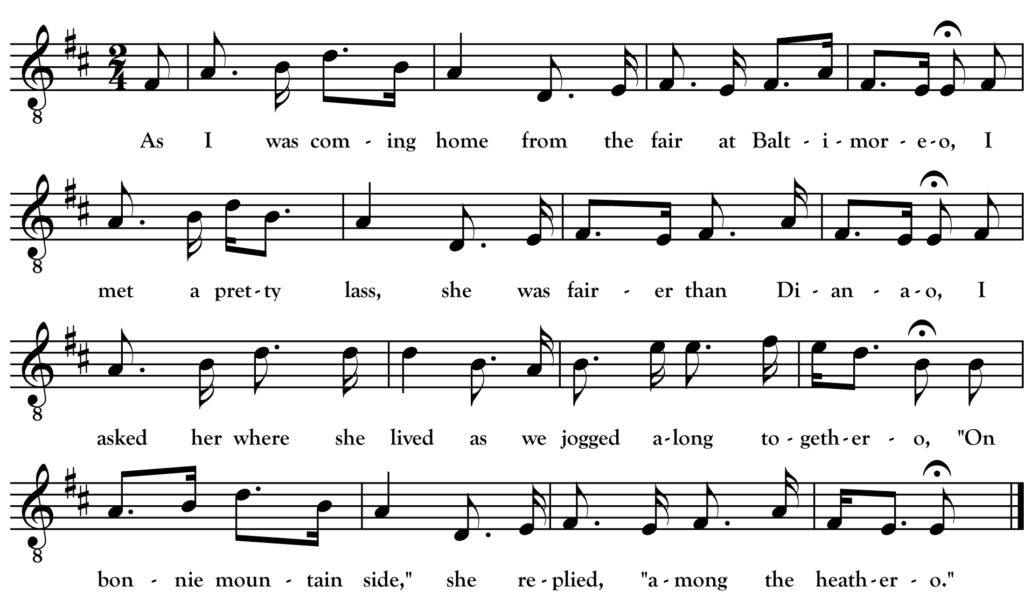

The Lass Among the Heather

As I was

coming home from the fair at Baltimor-e-o,

I met a pretty lass, she was fairer than Diana-o,

I asked her where she lived as we jogged along together-o,

“On bonnie mountain side,” she replied, “Among the heather-o.”

“Oh lassie

I’m in love with you, you have so many charms-o,

Oh lassie I’m in love with you, to you my bosom yearns-o,

A blink of your blue eye, your person is so charming-o,

Right gladly would I wed with you, dear lass among the heather-o.”

“Oh young

man do you think that I am so easy taken-o?

Oh young man do you think I believe what you are saying-o?

I’m happy and I’m well with my father and my mother-o,

‘Twould take a cunning lad for to coax me from the heather-o.”

“Oh lassie

condescend and do not be so cruel-o,

Oh lassie condescend grant a kiss to your own jewel-o,”

“If I should grant you one, you would surely want another-o,

So take it as you will, I’m the lass among the heather-o.”

This month’s song has been traced by Irish song scholar John Moulden back to its original County Antrim composer Hugh McWilliams (born 1783). McWilliams was a schoolmaster and prolific writer of songs that had an unusual knack for entering tradition including the well-travelled “When a Man’s in Love He Feels no Cold.” That song and “The Lass Among the Heather” both appear in McWilliams’ Poems and Songs on Various Subjects Vol. II, published in 1831. “The Lass Among the Heather” crossed over into Scotland where it enjoyed some popularity. It was also sung in Cork by Elizabeth Cronin and in the north woods of the United States.

My principle source for the above transcription was a version that appears in the book A Heritage of Songs compiled by Maine singer Carrie Grover (1879-1959) from her own family repertoire. The melody is entirely Grover’s (though it is similar to that given by Moulden in his pamphlet “Songs of Hugh McWilliams, Schoolmaster, 1831”). The text is a mix of Grover’s and the original printed by McWilliams. Both McWilliams and Grover sprinkle in some Scots language (hame, frae, amang, etc.) but I have cheated my version away from the Scots for the most part. I omitted Grover’s last verse (which doesn’t appear in McWilliams’ original) about the couple living happily ever after in favor of the ambiguous open-ended nature of Grover’s fourth verse.