Exile of Erin

“Oh, sad is my fate,” said the heart broken stranger,

“The wild deer and roe to the mountains can flee,

But I have no refuge from famine or danger,

A home and a country remains not for me;

Oh, never again in the green shady bower,

Where my forefathers lived shall I spend the sweet hours,

Or cover my harp with the wild woven flowers,

And strike the sweet numbers of Erin Go Bragh.

Oh, Erin, my country, though sad and forsaken,

In dreams I revisit thy sea-beaten shore,

But alas! in a far foreign land I awaken,

And sigh for the friends that can meet me no more;

And thou, cruel fate, will thou never replace me,

In a mansion of peace where no perils can chase me?

Oh, never again shall my brothers embrace me,

They died to defend me or live to deplore.

Where is my cabin once fast by the wildwood,

Sisters and sire did weep for its fall,

Where is the mother that looked over my childhood,

And where is my bosom friend, dearer than all?

Ah, my sad soul, long abandoned by pleasure,

Why did it dote on a fast fading treasure?

Tears like the rain may fall without measure,

But rapture and beauty they cannot recall.

But yet all its fond recollections suppressing,

One dying wish my fond bosom shall draw,

Erin, an exile bequeaths thee his blessing,

Land of my forefathers, Erin Go Bragh;

Buried and cold when my heart stills its motion,

Green be thy fields fairest Isle of the ocean,

And the harp striking bard sings aloud with devotion,

“Erin Mavourneen, sweet Erin Go Bragh.”

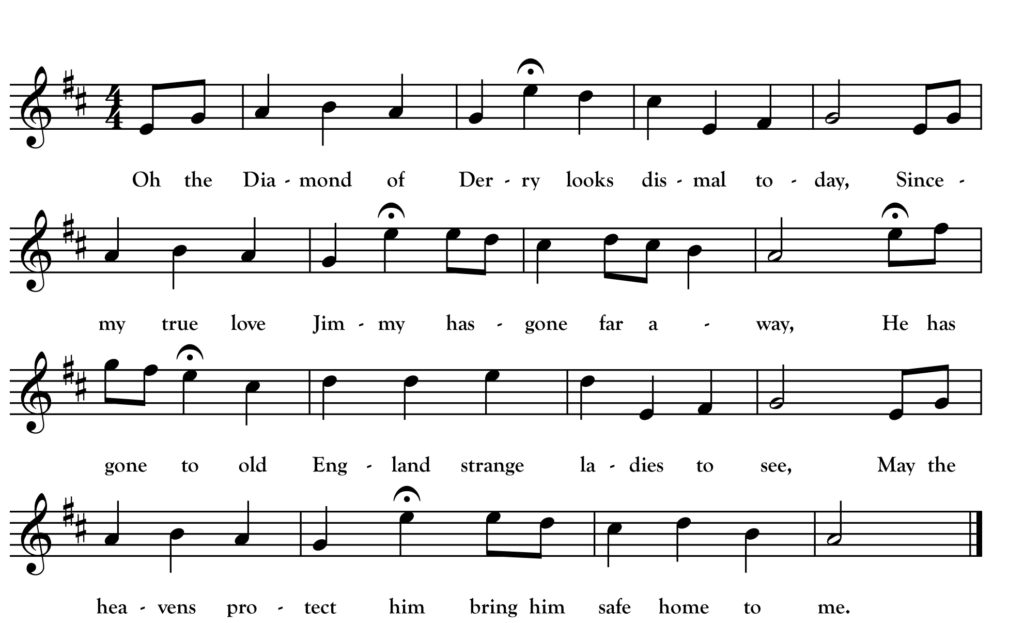

We return this month to the repertoire of Minnesota singer Michael Cassius Dean who printed “Exile of Erin” in his songster The Flying Cloud. Dean’s book reaches its 100th birthday next year having been printed in Virginia, Minnesota in 1922 while he was employed as night watchman for the Virginia-Rainy Lake Lumber Company mega-mill in that city. As I have written here before, Dean was visited by the wax cylinder recording machine of Robert Winslow Gordon in 1924 but his version of “Exile of Erin” does not appear to have been recorded at that time. We only have his text from the songster. The melody above is my own transcription of a version sung by Belle Luther Richards at Colebrook, New Hampshire for Helen Hartness Flanders in 1943. That recording is available on archive.org.

The Richards and Dean versions are the only versions collected from North American singers I have found. This is somewhat surprising given that the song was extremely popular in Ireland throughout the 1800s. It was popular enough to spark widely-publicized controversy over who wrote it! It seems fairly certain that the author was Scottish poet Thomas Campbell (1777-1844) who also authored “The Wounded Hussar.” Campbell reported that he wrote the song in 1800 in Hamburg after meeting a man named Anthony McCann who was exiled there for his role in the Rebellion of 1798.

It’s possible that Dean learned it from his Mayo-born parents. Mayo was a focus of action during the excitement of 1798 when French General Humbert landed with over 1000 troops at Cill Chuimín Strand, County Mayo in support of the revolutionaries in August of that year. It is also possible that Dean learned it from a source here in Minnesota. Minneapolis’ Irish Standard newspaper, to which Dean subscribed while living in Hinckley, printed the text of the song in 1886 and again in 1900.