Why Don’t My Father’s Ship Come In?

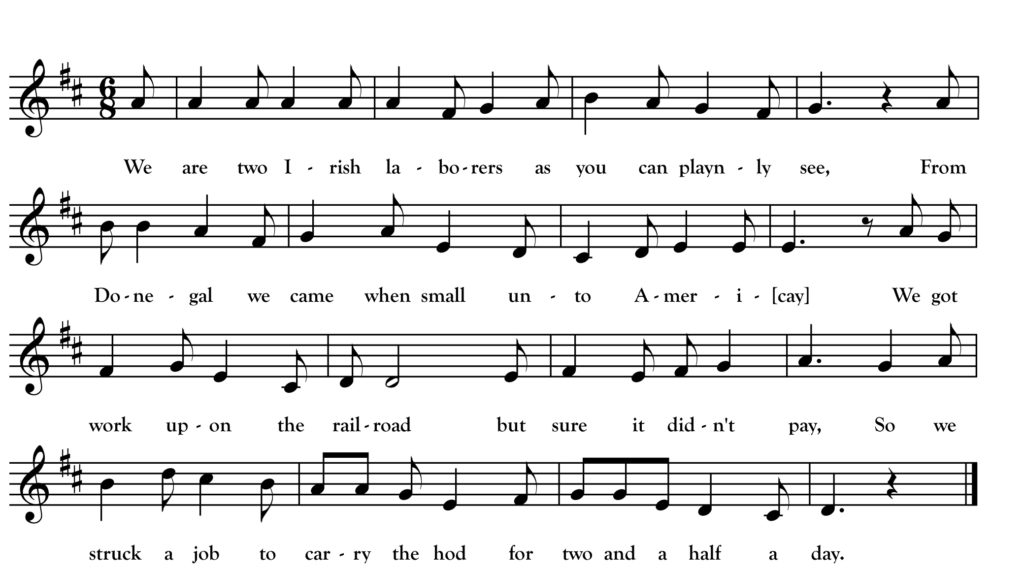

It was on a Christmas evening as I lay down to sleep,

I heard a boy of six years old on his mother’s knee did weep,

Saying “once I had a father dear who did me kind embrace

And if he was here, he would dry those tears flowing down my mother’s face”

Oh where is that tall and gallant ship that first bore him away,

With topsails soft and painted decks born by the breeze away,

While other ships are coming in splitting the icy foam,

Oh why don’t my father’s ship come in, and why don’t he come home?

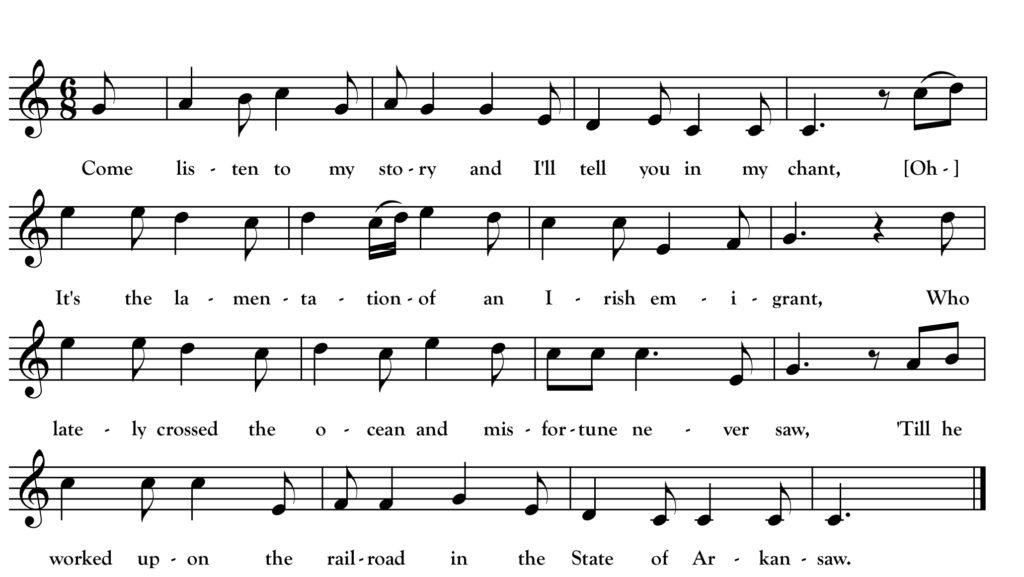

Oh, dear son, your father has tarried for to cross the stormy sea,

The ocean and the hurricane sweeps he’ll never come back to me,

Dear son your father’s dead and gone to the home of the brave,

The stormy ocean and winter winds sweep o’er your father’s grave

Oh well I do remember when he took me on his knee,

And gave me all the fruits he bore from off that India tree,

He said six months he would be gone and here leave us alone,

But by those stormy winter winds, twelve months are past and gone.

Oh hush my darling little son your innocent life is done,

Now you and I are all that’s left for to lament and mourn,

You are the darling of my heart I will press you to my side,

And they rose their eyes to heaven and the son and mother died.

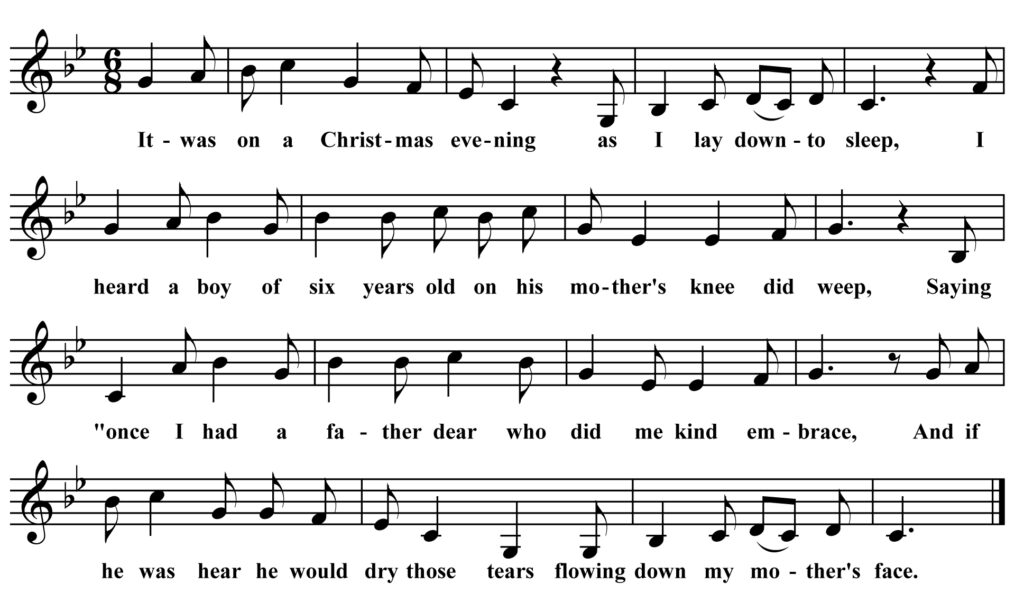

We return to Beaver Island, Michigan this month for a song from the repertoire of singer Johnny Green recorded by Alan Lomax during his 1938 visit to the island.

This dark and sorrowful lament for a father lost at sea appears in several collections across the north woods from the Canadian Maritimes to Ontario. Lomax’s recording of John Green is accessible via the Library of Congress website under the title (probably resulting from a mishearing of the first line) “Christmas Eve.”

Anita Best and Genevieve Lehr printed a version from Annie Green of Newfoundland in their book Come & I Will Sing You. Annie Green closed the song this way:

“My boy you’re the pride of all my heart,” as she pressed him to her breast,

And closed her eyes to the yonder skies where the weary ones find rest.