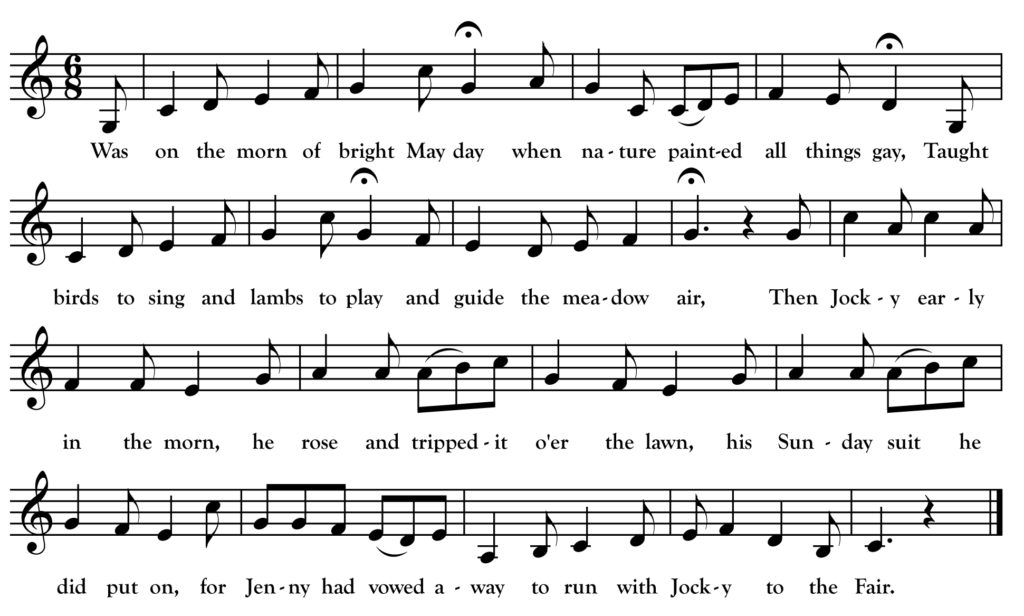

Jocky to the Fair

Was on the morn of bright May day when nature painted all things gay,

Taught birds to sing and lambs to play and guide the meadow air,

Then Jocky early in the morn,

He rose and tripped it o’er the lawn,

His Sunday suit he did put on,

For Jenny had vowed away to run with Jocky to the Fair.

The village parish bells had rung with eager steps he trudged along,

His flowery garment round him hung that shepherds used to wear,

Tapped at the window, “Haste my dear,”

When Jenny impatient cried, “Who’s there?”

“It’s me my love, there’s no one here,

Step lightly down, you need not fear with Jocky to the Fair.”

“My dad and mother is fast asleep, my brothers are up and with the sheep,

So will you still your promise keep that I have heard you swear?

Or will you ever constant prove?”

“I will by all that’s good, my love,

I’ll never deceive my charming dove,

Return those vows in haste my love with Jocky to the Fair.”

Then Jocky did his vows renew, they pledged their words and away they flew,

O’er cowslip bells and balmy dew and Jocky to the Fair,

Returned there’s none so fond as they,

They blessed that kind perpetual day,

The smiling month of blooming May,

When lovely Jenny ran away with Jocky to the Fair.

[repeat first verse]

In the world of competitive Irish step dancing, the tune “Jockey to the Fair” is one of the seven approved and strictly regulated traditional set dances. The tune, it turns out, originated with a popular English song of the 18th century. It is somewhat ironic that the melody has ended up on this short list of official tunes in a realm so historically sensitive to maintaining Irish cultural purity! Of course, recent cultural historians have been increasingly willing to admit that melodies (and lyrics) have travelled back and forth between the two islands for centuries and that the Irishness of a song or tune is complex to calculate (and possibly not worth the effort). To this day, “Jock(e)y to the Fair” is a favorite of uilleann pipers and Morris dancers all over the world.

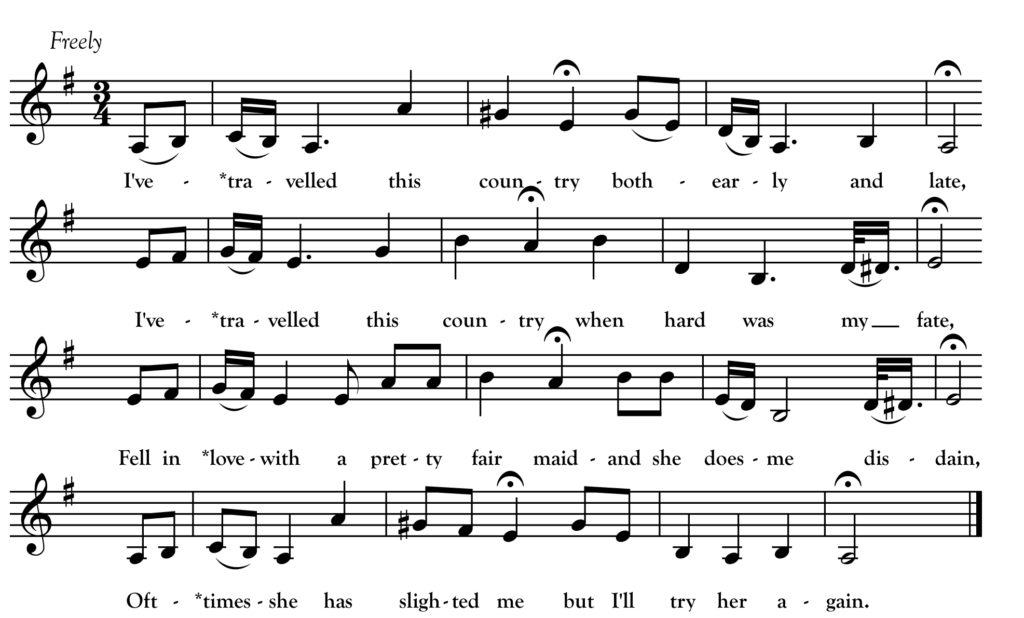

The song that accompanies the melody (or at least a close variant of the dance tune) is rarely heard in Irish circles so it was interesting to find it in Helen Creighton’s Nova Scotia recordings as sung by Irish-Canadian Edmund Henneberry of tiny Devil’s Island—a now-deserted island in Halifax harbor. You can hear Henneberry sing it on the album Folk Music from Nova Scotia which is available online via Smithsonian Folkways. My transcription was made from that recording.