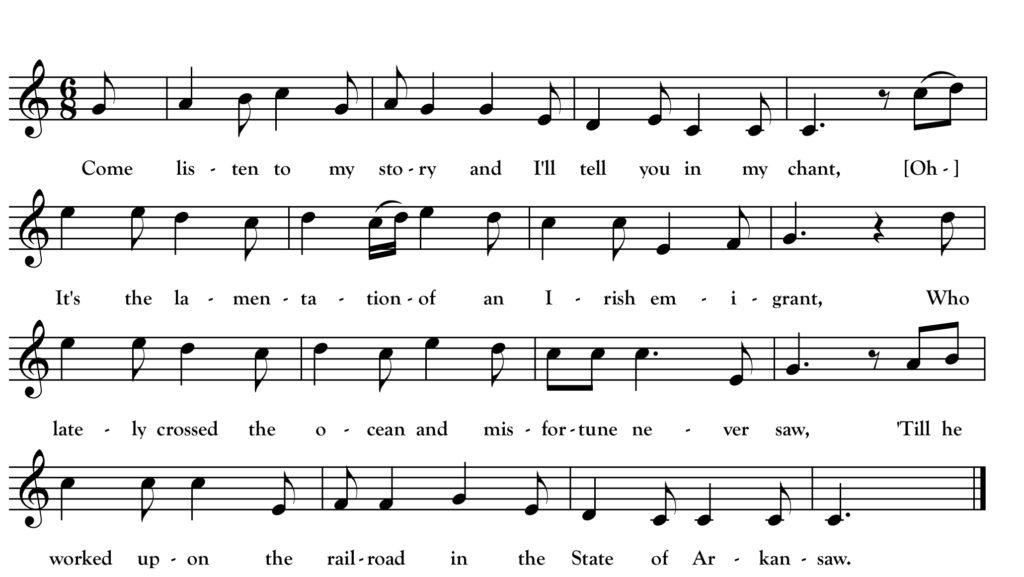

The Arkansaw Navvy

Come listen to my story and I’ll tell you in my chant

It’s the lamentation of an Irish emigrant,

Who lately crossed the ocean and misfortune never saw,

’Till he worked upon the railroad in the State of Arkansaw.

When I landed in St. Louis I’d ten dollars and no more,

I read the daily papers until both me eyes were sore;

I was looking for advertisements until at length I saw

Five hundred men were wanted in the State of Arkansaw.

Oh, how me heart it bounded when I read the joyful news,

Straightway then I started for the raging Billie Hughes;

Says he, “Hand me five dollars and a ticket you will draw

That will take you to the railroad in the State of Arkansaw.

I handed him the money, but it gave me soul a shock,

And soon was safely landed in the city of Little Rock;

There was not a man in all that land that would extend to me his paw,

And say, “You’re heartily welcome to the State of Arkansaw.”

I wandered ’round the depot, I rambled up and down,

I fell in with a man catcher and he said his name was Brown;

He says “You are a stranger and. you’re looking rather raw,

On yonder hill is me big hotel, it’s the best in Arkansaw.”

Then I followed my conductor up to the very place,

Where poverty was depicted in his dirty, brockey face;

His bread was corn dodger and his mate I couldn’t chaw,

And fifty cents he charged for it in the State of Arkansaw.

Then I shouldered up my turkey, hungry as a shark,

Traveling along the road that leads to the Ozarks;

It would melt your heart with pity as I trudged along the track,

To see those dirty bummers with their turkeys on their backs.

Such sights of dirty bummers I’m sure you never saw

As worked upon the railroad in the State of Arkansaw.

I am sick and tired of railroading and I think I’ll give it o’er,

I’ll lay the pick and shovel down and I’ll railroad no more;

I’ll go out in the Indian nation and I’ll marry me there a squaw,

And I’ll bid adieu to railroading and the State of Arkansaw.

“Navvy,” from “navigational engineer,” was a common 19th century term for a railroad worker. Singer Michael Dean, the source of the text above, had many connections to the railroad and railroad work. Dean tended bar for years at saloons that catered to railroad workers in Hinckley, Minnesota. His older brother James was a lifelong conductor for the Milwaukee Road based in Milwaukee and older brother Charles worked for the Milwaukee Road in Minnesota and South Dakota based out of Minneapolis. According to The History of South Dakota, Vol. 2 by Doane Robinson, Charles Dean helped build the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul railroad from Glencoe, MN to Aberdeen, SD from 1879-1881.

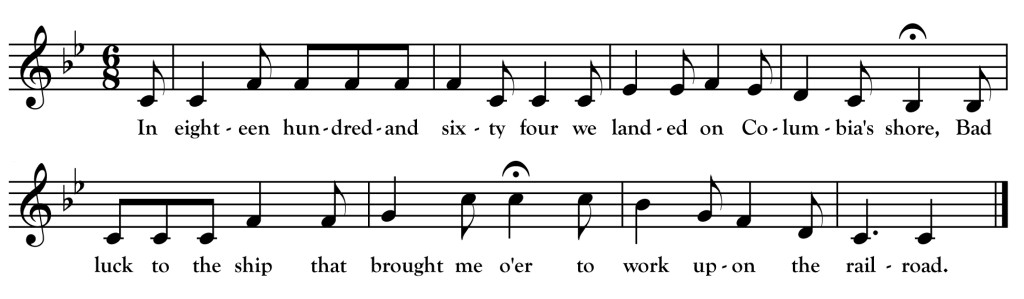

Dean’s songster, The Flying Cloud, includes four lyrics about railroad workers: “Jerry Go Oil the Car,” “The Grave of the Section Hand,” “O’Shaughanesey” and “The Arkansaw Navvy.” A fifth, “To Work Upon the Railroad” appears among the 1924 wax cylinder recordings of Dean singing.

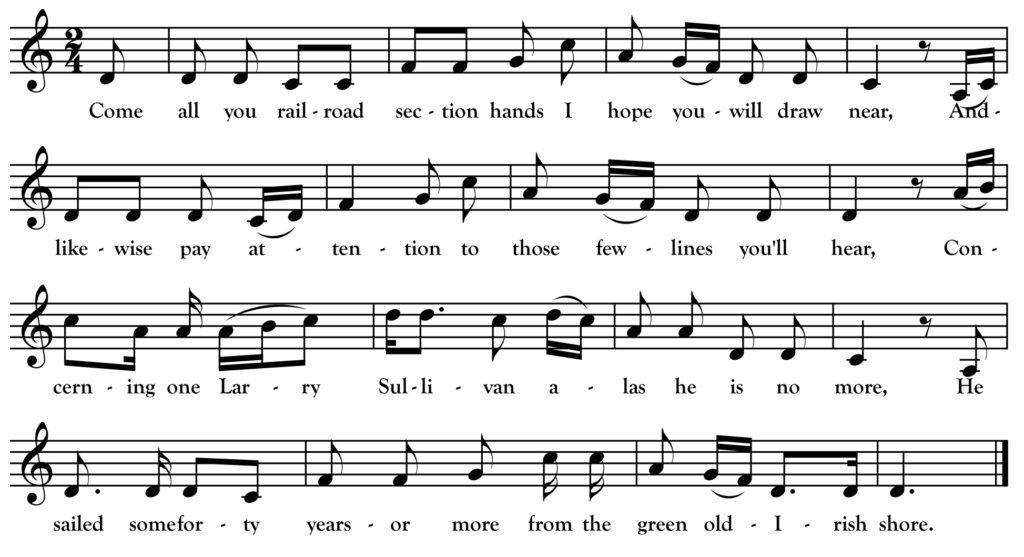

Since Dean’s melody for “The Arkansaw Navvy” is unknown, I used a melody sung by Newfoundland singer Paddy Duggan as recorded by MacEdward Leach and available online. The song was likely North American in origin and it appears in many collections from the US. Interestingly, an Irish version does appear in Sam Henry’s Songs of the People. Henry’s informant was Jack McBride of Kilmore, Co. Antrim who learned it from a sailor.