Tidy Irish Lad

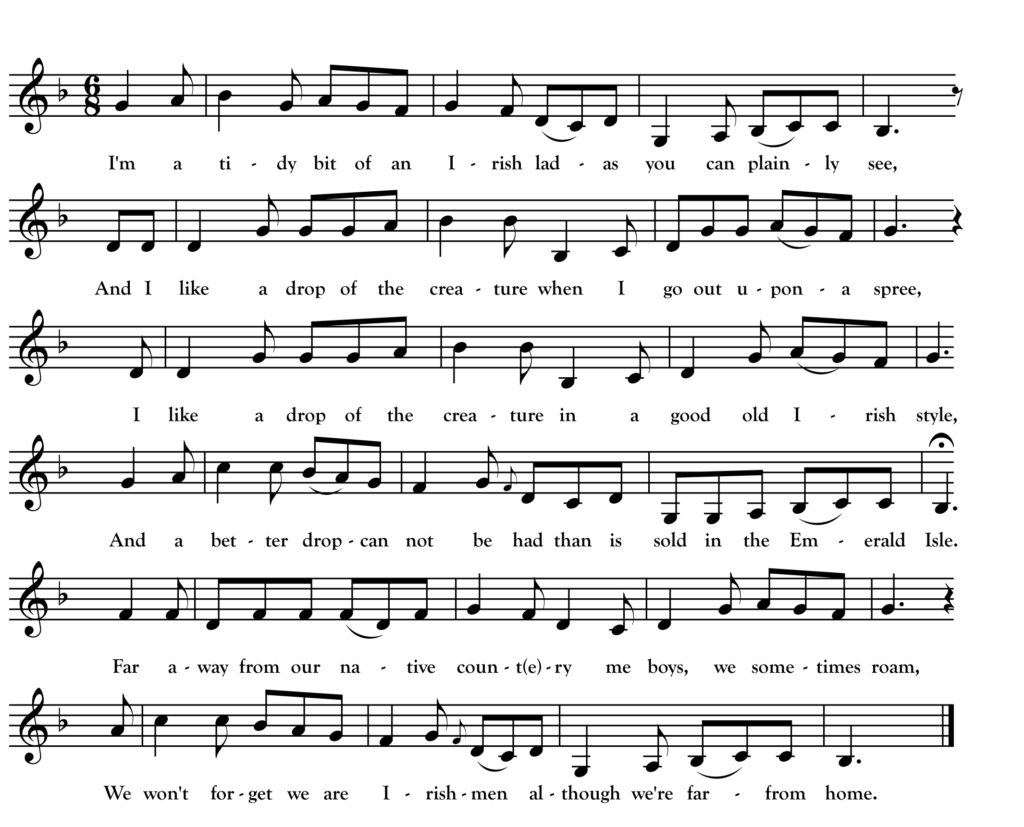

I’m a tidy bit of an Irish lad, as you can plainly see,

And I like a drop of the creature when I go out upon a spree;

I like a drop of the creature in a good old Irish style,

And a better drop cannot be had than is sold in the Emerald Isle.

Chorus—

Far away from our native country, me boys, we sometimes roam,

We won’t forget we are Irishmen, although we’re far from home.

Oh, they say no Irish need apply, it is a thing I don’t understand,

For what would the English army do if it were not for Paddy’s land?

Whenever they went to battle they never were known to win,

Except when the ranks they were filled up with the best of Irishmen.

It was at the battle of Waterloo, Sebastapool the same,

The sons of Paddy’s land they showed that they were game;

They gave three hearty cheers, me boys, in a good old Irish style,

And we walloped the Russians at Inkerman, did the boys of the Emerald Isle.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the song book printed by Irish-Minnesotan Michael Dean. Its front cover reads: The Flying Cloud And 150 Other Old Time Poems and Ballads: A Collection of Old Irish Songs, Songs of the Sea and Great Lakes, The Big Pine Woods, The Prize Ring and Others. This June will also mark ten years that I’ve been writing Northwoods Songs. Most of the early columns were about Dean’s songs and I will return to Dean this year in honor of his book’s centennial. I continue to be fascinated by Dean’s story and music (there are actually 166 songs in his book and I have written about 37 of those here so far).

This month’s song is one that took some real digging to research but I recently had a breakthrough. Dean prints “The Tidy Irish Lad” in The Flying Cloud before the song “No Irish Wanted Here” and the two songs have an interesting relationship. Both reference versions of the much-discussed “No Irish Need Apply” that appeared in newspaper help wanted ads in 1850s New York and has exemplified anti-Irish discrimination for generations since. Several songs were written that mention variants of this phrase and these added, no doubt, to its prominent place in cultural memory. The most well-known “No Irish Need Apply” songs seem to have originated in the early 1860s in New York and possibly in England around the same time. “No Irish Wanted Here” was a take-off on this, by then, established theme penned by the great New York performer Ed Harrigan and debuted in January, 1875.

“The Tidy Irish Lad” may have been an early Dublin take on the theme. A broadside estimated to have originated in Dublin around 1870 and digitized by the National Library of Scotland titled “A New Song Call’d the Boys of the Emerald Isle” matches Dean’s text with an extra verse about Irish dance and music:

In Ireland you will see the boys [c]an dance a jig or reel,

With their pretty little colleen can shove both toe and heel,

The piper sits to play a tu[n]e to make the people smile,

While we dance our native musi[c] does the boys of the Emerald Isle.

I was delighted to discover that the song also appears in the repertoire of legendary Irish singer Paddy Tunney. Tunney sings a version very similar in text to Dean’s beginning “I’m a tight little bit of an Irish lad” which you can hear online (starts at 39:29) via the Peter Kennedy collection at the British Library. I combined Tunney’s melody with Dean’s text above.

Broadside image from National Library of Scotland. Shelfmark Crawford.EB.2391