The Irish American Club

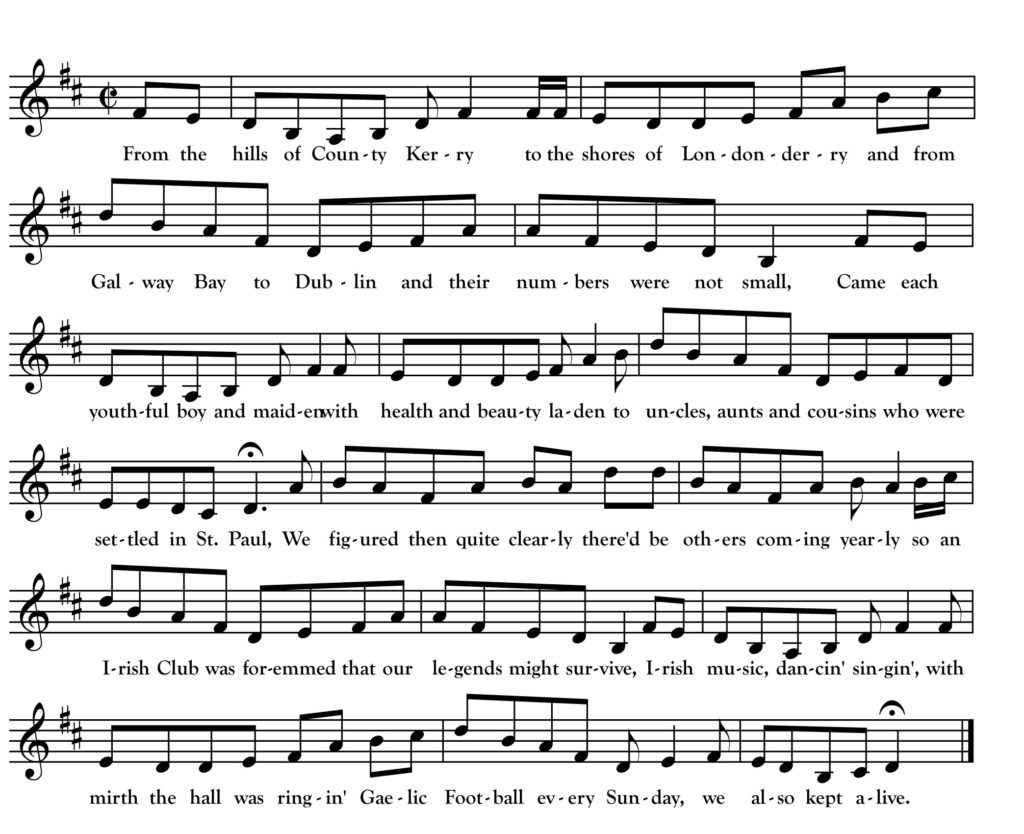

From the hills of County Kerry to the shores of Londonderry,

And from Galway Bay to Dublin and their numbers were not small,

Came each youthful boy and maiden, with health and beauty laden,

To uncles, aunts, and cousins who were settled in St. Paul.

We figured then quite clearly, there’d be others coming yearly,

So an Irish club was formed that our legends might survive,

Irish music, dance, and singin’ with mirth the hall was ringin’,

Gaelic football every Sunday we also kept alive.

It was healthy, wholesome living–music, dancing, taking, giving,

We were always looking forward, eager for the next event,

Telephones kept hummin’ about doings’ that were comin’,

We kept the boys and girls feeling happy and content.

Old timers watched us proudly and proclaimed in accents loudly

We were the best they ever saw in any park or hall,

With gestures and with glances they supervised the dances,

While sittin’ on the benches lined up along the wall.

And what with all the dances there was quite a few romances,

The wedding bells kept ringing through the summer and the fall,

And I know the angels blessed them as friends and kin caressed them,

When the ceremonies was over and we gathered at the hall.

There were some we watched them nightly, looking bashful talking quietly,

But a little drop of poteen worked magic I declare,

The shyful blush it vanished, the feeling blue was banished,

And they would exhibit talents we never knew was there.

With the officers commanding our club began expanding,

We did a mighty lot of good in a quiet and humble way,

The mission house was cherished, and the orphan house was nourished,

We shared the joys and sorrows of our people day by day.

But half the pride of living is the heart-felt joy of giving,

Our club has been rewarded with treasures more than gold,

We are known and are respected, and by rich and poor accepted,

And Christian Irish people keep flocking to our fold.

We all feel quite elated at how high our club is rated,

The part that I donated I feel is rather small,

It will always give me pleasure, fond thoughts I’ll always treasure,

Of friendships true and wholesome, cultivated in St. Paul.

We will prove our reputation to our people round the nation,

Let no jealousy or discord within our ranks prevail,

We’ll show our hospitality to every nationality,

And our fame will be re-echoed to the shores of Innisfail.

We bring things home to St. Paul, Minnesota this week for a fascinating local song composed by Irish immigrant Patrick Hill (1900-1980) who came to St. Paul from County Tipperary (by way of Canada) in 1923. Hill was one of the founders of the Twin Cities Irish American Club that was active here from the post-World War II years through the 1980s. He was also a fiddle player and a prolific poet.

The Eoin McKiernan Library, of which I am the director, is working on an exhibition on The Irish American Club. From newspaper research, we know the club held weekly, Saturday night dances at the Midway Club (1931 University Avenue) starting in 1949, moved most events to the Uni-Dale Commercial Club at 345 ½ University Ave. in 1953 and then moved again to Ford Union Hall at 2191 Ford Pkwy in 1962. Their activity seems to have tapered off after the 1960s though they were instrumental in some of the first Irish Festivals organized in the early 1980s.

Hill’s song captures the mission and story of the club quite well—painting a picture of Irish immigration in the post-war period that matches well with accounts I have read from Boston and other American cities.

If you or someone you know has knowledge or photos of the Irish American Club, please contact me (Brian Miller) at 651-245-3719 or library@celticjunction.org