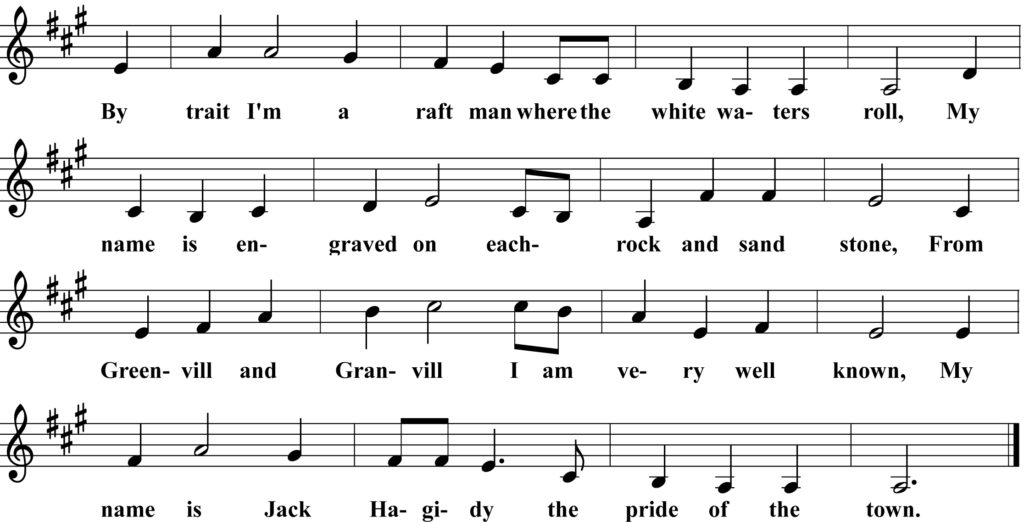

By Trait I’m a Raftsman (Jack Haggerty)

By trait I’m a raftman, where the white waters roll,

My name is engraved on each rock and sand stone,

From Greenvill to Grandvill I am very well known,

My name is Jack Hagidy the pride of the town.

My troubles I will tell you without any delay,

Of a dear little damsel my heart stole away,

She was the black’s Smith only daughter by the flat River side,

And I always intended for to make her my bride.

I dressed her in jewels embroiderys and lace,

And the costliest velvet her eyes could embrace,

I took her to dances to parties and Balls,

And Sundays boat riding where the white waters roll.

I worked on the River till I made quite a stake,

I was sturdy and steadfast neither gambled nor drank,

I gave her my wages the same to keep safe,

I begrudged that girl nothing that I had on this earth.

One day in Plat River a letter I received,

Saying defy all good promises, my self I realise,

She was married to another not long delay,

And the next time I saw her she would ne’er be a maid.

Her mother Jane Tucker I lay all the blame,

She has caused her to leave me and blackened my name,

She has cast off the rigens that God soon would tie,

And have left me a rambler untill the day that I die.

Not it is here in Plat River for me there’s no rest,

I will sholder my Pevie and I will go West,

I will go to mont Sagin [?] toward the red setting sun,

Leave behind me Plat River and the false hearted one.

Now come all ye bold Raftmen with hearts brave and true,

Don’t depend on a women for your left if you do,

And when that you see one with chestnut brown curls,

Just think of Jack Hagidy and the Plat River girl.

Over the last 17 years I have performed Minnesota-sourced folksongs in over a hundred venues spread over 32 counties in Minnesota, primarily with Randy Gosa as The Lost Forty. I love bringing these songs back to the communities they came from and, occasionally, an audience member will share a story of music in their own family with me after the show.

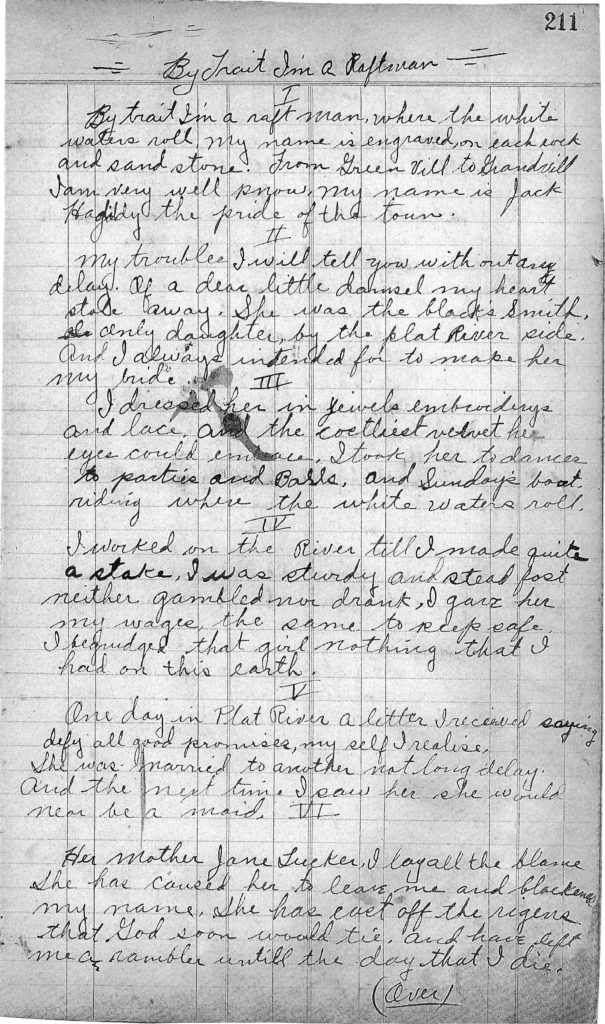

In 2022, Eleanor Hall of Clearbrook, Minnesota found me after a performance in Shevlin to tell me about a handwritten songbook kept by her mother Alma Pitsenburg Doten. Alma was born in 1904 in Moose Creek Township, 12 miles west of where I grew up on Grant Lake west of Bemidji! This April, I was able to meet up with Eleanor and make scans of her mother’s fascinating book. There are over one hundred songs written in pencil in an old ledger book kept with love and reverence all these years.

I was delighted to find a few lumberjack ballads in Alma’s book. “Jack Haggerty” was the first song in Franz Rickaby’s 1926 book Ballads and Songs of the Shanty-Boy. Rickaby wrote that the song “is native to the Flat River in southern Michigan” and that it “was a great shanty favorite and is still widely met with in the Lake states.” Rickaby printed four versions of the song including two collected from Bemidji-based singers. Alma called the song “By Trait I’m a Raftman.”

Above, I have transcribed Alma Pitsenburg Doten’s text complete with some irregular spellings found in her songbook. I matched it with a rather unique (and nice!) variant of the song’s melody recorded by Helen Hartness Flanders from the singing of Jack McNally at Stacyville, Maine in 1942. The McNally recording is available online via archive.org.