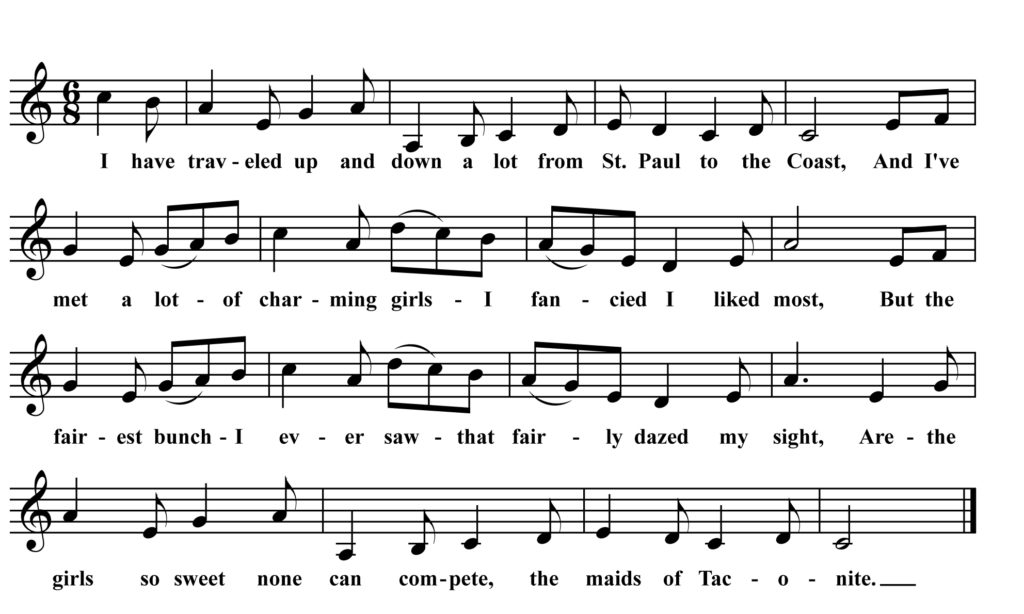

To the Maids of Taconite

I have traveled up and down a lot,

From St. Paul to the Coast,

And I have met a lot of charming girls,

I fancied I liked most.

But the fairest bunch I ever saw,

That fairly dazed my sight,

Are the girls, so sweet, none can compete,

With the maids of Taconite.

They always look so graceful,

Each wears a pleasing smile,

They are just the size to take the prize,

They dress in neatest style.

And if you are fond of dancing,

It would fill you with delight,

To have a whirl with any girl,

From the town of Taconite.

But I feel sorry for the boys,

That are sticking to their Ma,

For what is life without a wife,

And a tot to call you pa?

My college chums, take my advice,

And you will find this world more bright,

If you will set the day, not far away,

With a maid from Taconite

If you are just her cousin,

Give some other guy fair play,

Don’t aggravate and have her wait,

Until her hair turns gray.

So, girls, don’t be too patient,

Demand what’s just and right,

The girls are few that equal you

You maids of Taconite.

So, here’s good luck to each fair maid,

In that little mining town,

When you are in their company,

No face could wear a frown.

May each one wed some level head,

For love, and not for spite,

So, now, adieu, good luck to you,

The maids of Taconite.

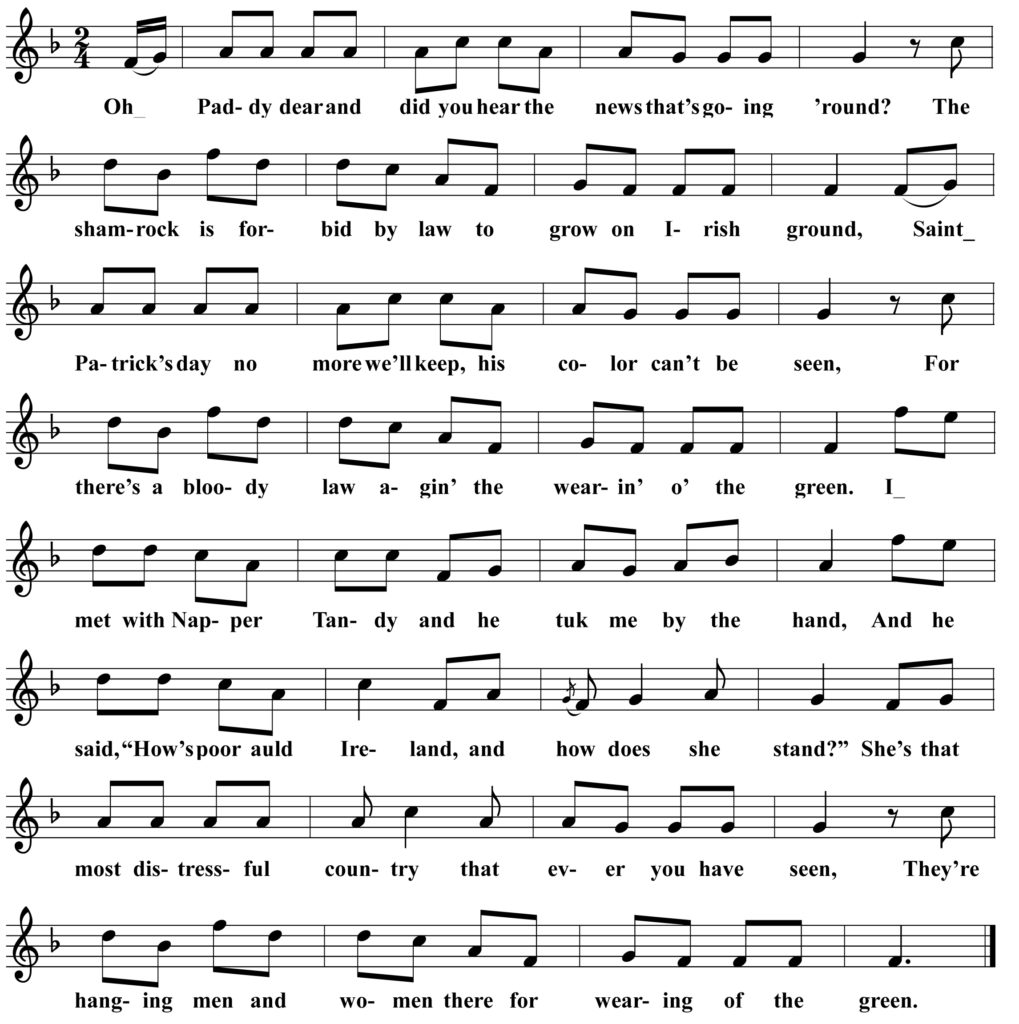

Readers of this column will know that I am always on the hunt for Irish-style songs that include Minnesota place names and stories. In 15 years of searching, I have found a handful here and there. In my experience, Minnesota singers were more likely to sing about Ireland or places in Michigan or Ontario than they were to reference the North Star State itself.

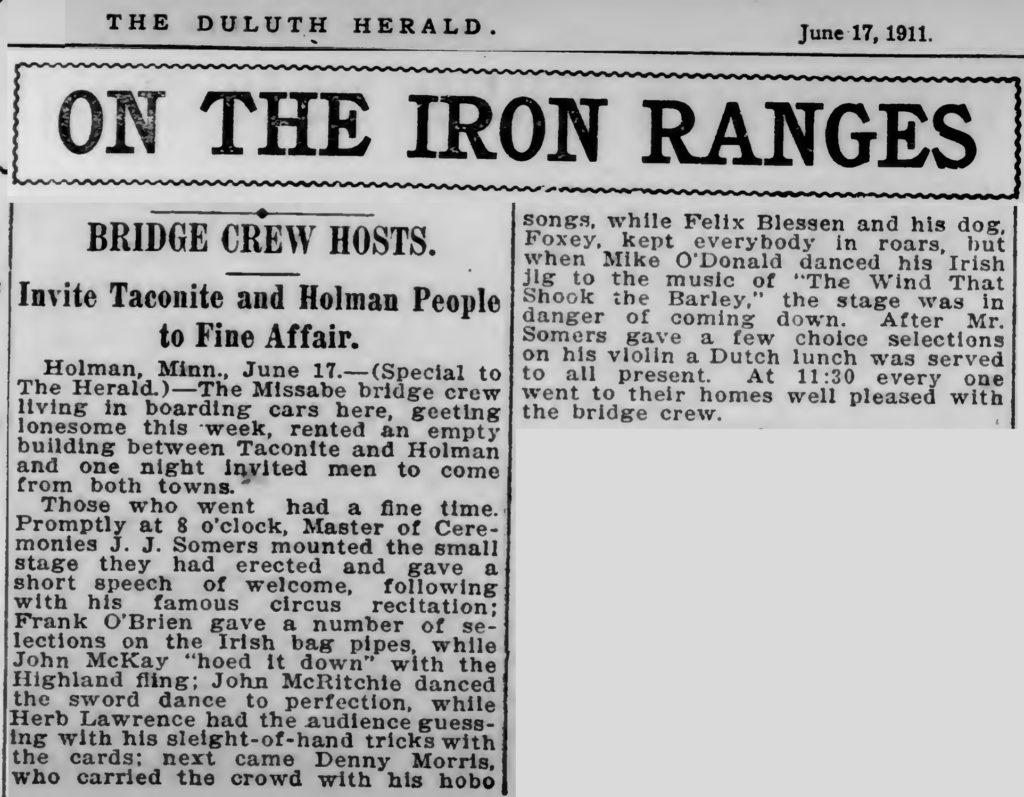

Last month, I found a real gold mine! I first saw the name J.J. Somers when local piper Tom Klein shared a fascinating paragraph found in the Duluth Herald of June 17, 1911:

There are a lot of intriguing references in that piece!

It turns out that James J. Somers was born to Irish parents in the Georgian Bay region of Ontario in 1865. His home address was in Bottineau County, North Dakota in 1911 and his job on the bridge crew was one of many seasonal gigs he took from Seattle to Iowa to Minnesota during his life. He left North Dakota for the Twin Cities permanently in 1913, settling eventually in Robbinsdale. He also, I recently discovered, published a book of songs and poems he had written in 1913. The book, Jim’s Western Gems, is fully available on the Internet Archive!

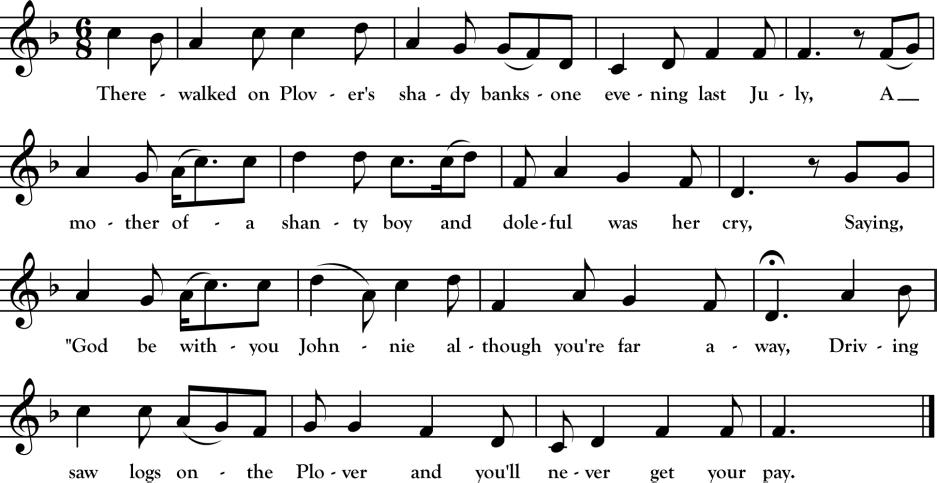

“To the Maids of Taconite” appears in the book and is dated 1911 so it must have been composed around the same time as the raucous party described in the Duluth newspaper. Most songs in Somers’ book do not reference any melody. For this one, I took a melody from an unpublished songbook Songs of the Dogwatch compiled by Joseph McGinnis, another Irishman from Ontario and from the same generation as Somers. The air is that used by McGinnis for “The Banks of Claudy.”

I expect to share more songs and research on Jim Somers in the months to come!