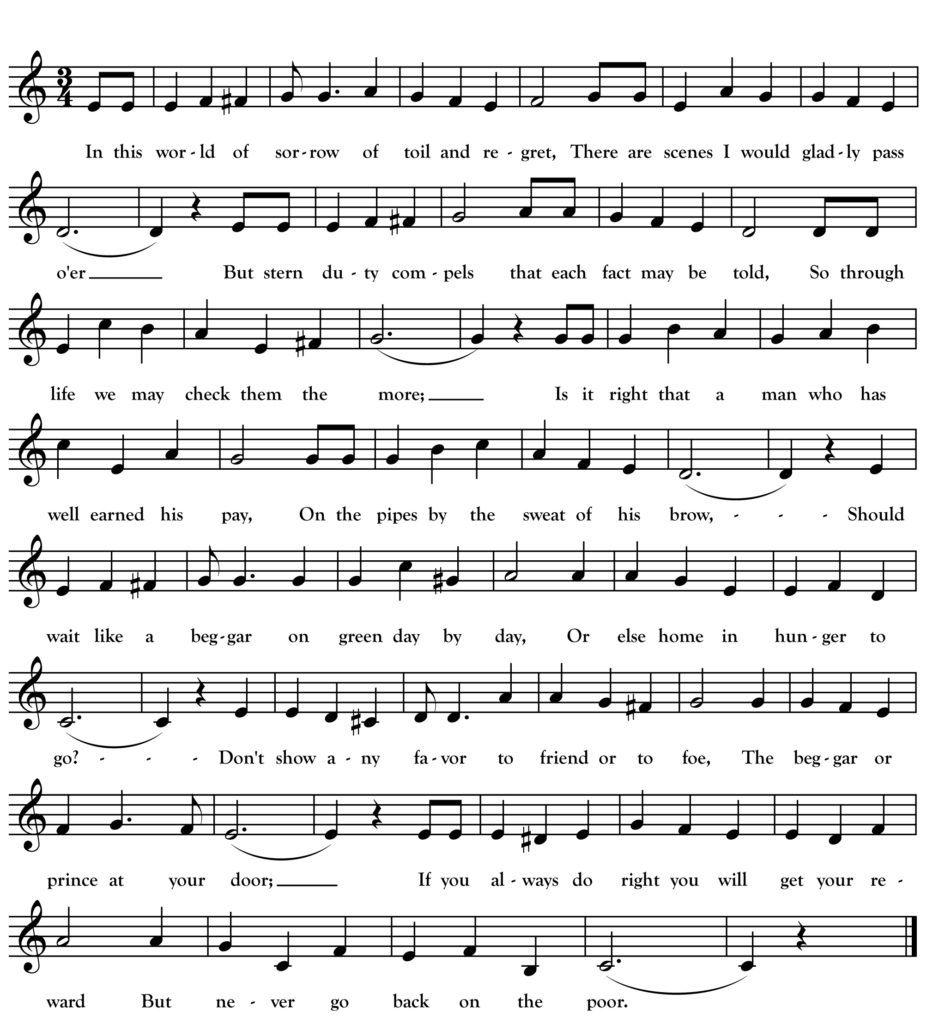

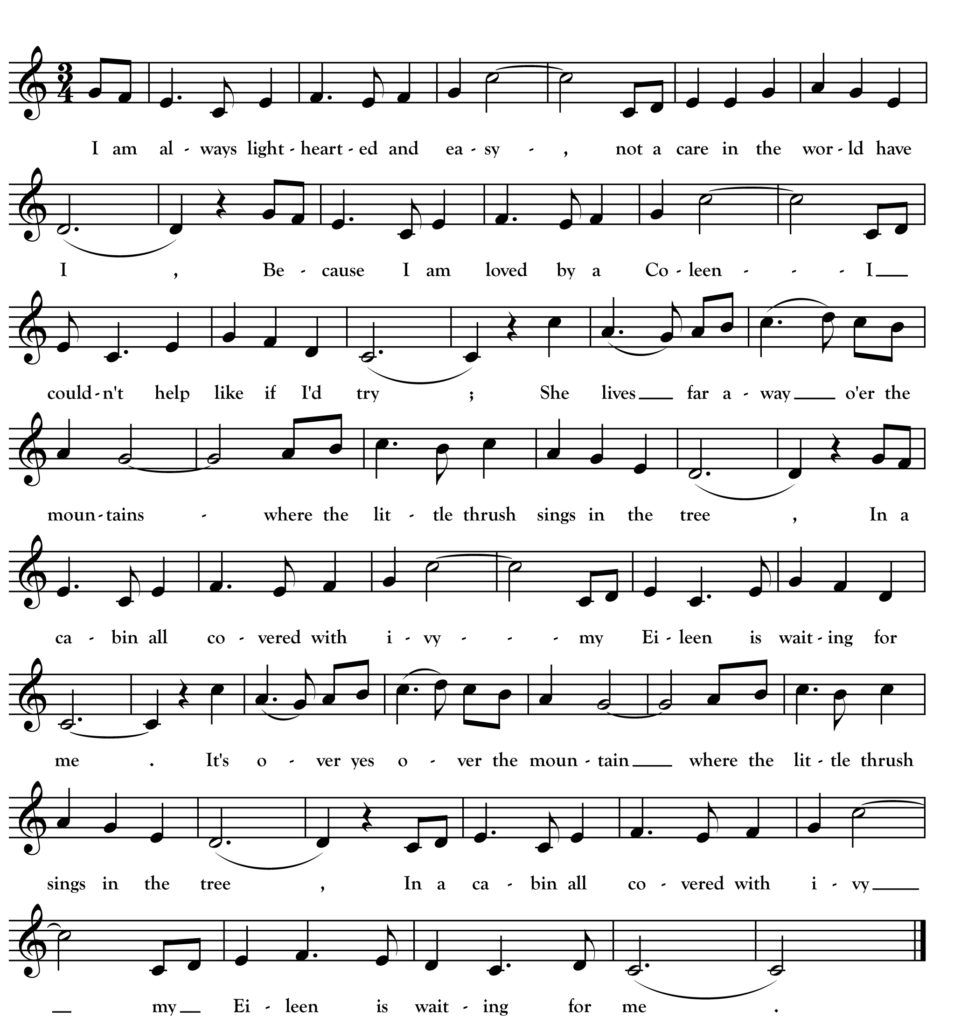

My Eileen is Waiting for Me

I am always light hearted and easy, not a care in the wide world have I,

Because I am loved by a Coleen I couldn’t help like if I’d try;

She lives away over the mountains where the little thrush sings in the tree,

In a cabin all covered with ivy my Eileen is waiting for me.

Chorus—

It’s over, yes over the mountain where the little thrush sings in the tree,

In a cabin all covered with ivy my Eileen is waiting for me.

The day I bid good-bye to Eileen, that day I will never forget,

How the tears bubbled up from their slumber, I fancy I’m seeing them yet;

They looked like the pearls in the ocean as she wept those tears of love,

Saying, “Barney, my boy, don’t forget me until we meet again here or above.”

Though mountains and seas may divide us and friends like the flowers come and go,

Still these thoughts of my Eileen will cheer me and comfort wherever I go,

For the imprints of love and devotion, surrounded by thoughts that are pure,

Will serve as a guide to the sailor while sailing the wild ocean o’er.

———-

With the passing of beloved musician Martin McHugh this past month, I chose a song that was a favorite of his. Martin played “My Eileen is Waiting for Me” as a waltz at countless sessions and dances and would sometimes sing bits of the words if you were lucky!

It turns out this song has a long history in Minnesota. Mike Dean printed his version in his 1922 songster The Flying Cloud under the title “Allanah is Waiting for Me” (a curious and possibly misprinted title because in Dean’s actual song lyric the name is Eileen). It was also in the repertoire of Ontario singer O.J. Abbott who called it “Over the Mountain.”

“Over the Mountain” was the original title when, in 1882, the song was composed by celebrity tenor William J. Scanlan, a second generation Irishman from Springfield, Massachusetts. Scanlan sang it in the play “Friend or Foe” which he performed at the Grand Opera House in Saint Paul in April 1885. The song reached Ireland by the early 1900s where it was found in a County Cavan manuscript in 1905. By the 1920s, the song’s melody and sections of its lyrics began a new life in American country music after a recording by Uncle Dave Macon and a rewrite, by Fiddlin’ John Carson, called “The Grave of Little Mary Phagan.”

Dean’s melody is unrecorded but Abbott sang it to a similar melody to that used by Martin McHugh. The above is a marriage of Dean’s words from 1922 with McHugh’s melody circa 2022 (based on McHugh’s album The Master’s Choice.)