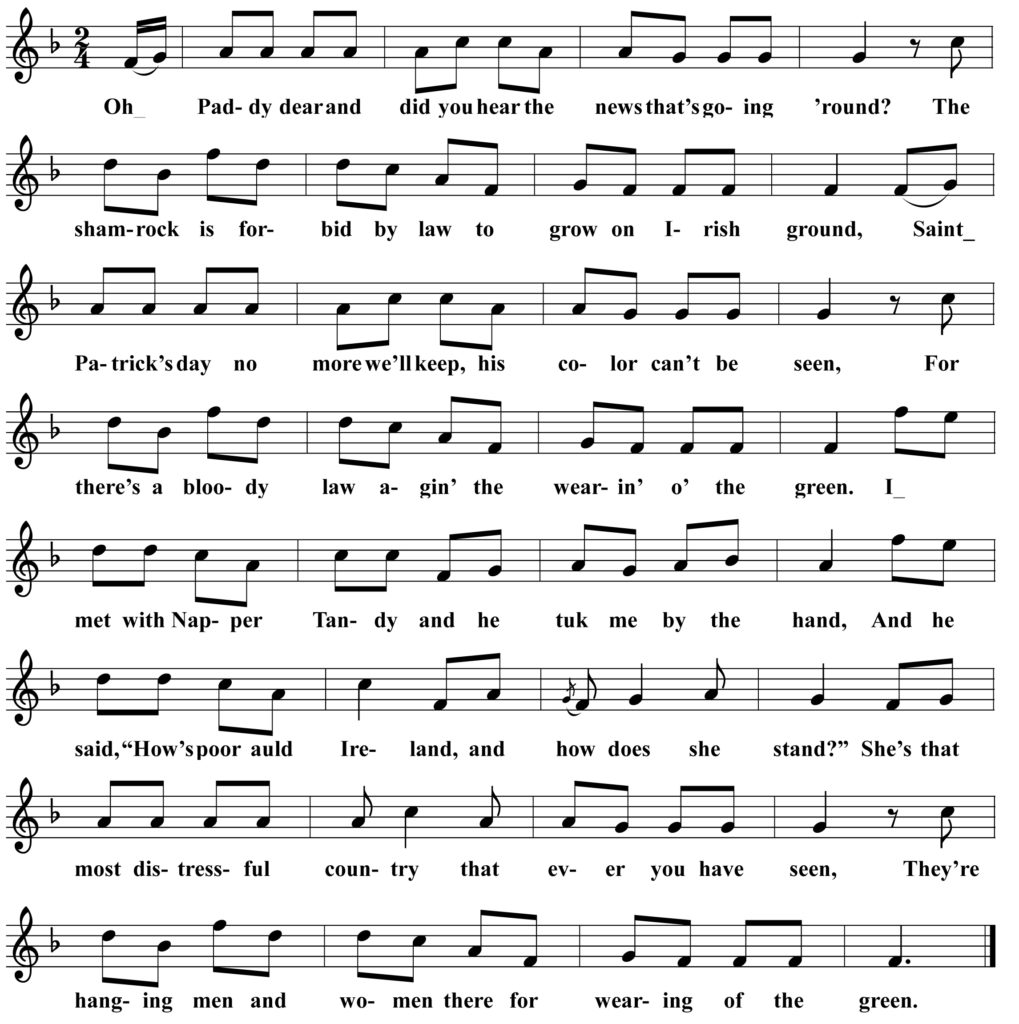

Wearing of the Green

Oh, Paddy, dear, and did you hear the news that’s going ’round?

The shamrock is forbid by law to grow on Irish ground;

Saint Patrick’s day no more we’ll keep, his color can’t be seen,

For there’s a bloody law agin’ the Wearin’ o’ the Green.

I met with Napper Tandy and he tuk me by the hand,

And he said, “How’s poor auld Ireland, and how does she stand?”

She’s that most distressful country that ever you have seen,

They’re hanging men and women there for wearing of the green.

Then since the color we must wear is England’s cruel red,

Sure, Ireland’s sons will ne’er forget the blood that they have shed;

You may take the shamrock from your hat, and cast it on the sod,

But ’twill take root and flourish still, tho’ under foot ’tis trod;

When the law can stop the blades of grass from growing as they grow,

And when the leaves in summer time their verdure dare not show,

Then I will change the color I wear in my caubeen,

But till that day, please God, I’ll stick to wearing of the green.

But if at last our color should be torn from Ireland’s heart

Her sons in shame and sorrow from the dear old soil will part,

I’ve heard whisper of a country that lies far beyant the say,

Where rich and poor stand equal in the light of freedom’s day;

Oh, Erin, must we lave you, driven by a tyrant’s hand,

Must we seek a mother’s welcome from a strange but happy land!

Where the cruel cross of England’s thralldom never shall be seen,

And where, in peace, we’ll live and die, a-wearing of the green.

We have a Minnesota text this month for the long-popular Irish patriotic song “The Wearing of the Green.” Dublin-born stage singer and theatrical innovator Dion Boucicault composed this song in 1865, borrowing the “wearing of the green” refrain, the last half of the first verse and possibly the melody from an existing song dating to the 1798 rebellion. The earlier song, as printed by H. Halliday Sparling in Irish Minstrelsy (c. 1887), has the protagonist fleeing to France where Napoleon himself asks “How is old Ireland and how does she stand?” Boucicault moved the land of refuge to America: the land “far beyant the say, where rich and poor stand equal in the light of freedom’s day.”

Though lovers of traditional songs sometimes lose interest when a song is revealed to have originated on the commercial stage, there is much to be learned and appreciated from the context of these songs. The late, great scholar of Irish-American song Mick Moloney says Boucicault, an international superstar in his day, “single-handedly upgraded the popular image of the Irish male in this country during the 1860s.” At a time when stereotypical, buffooning Irish characters dominated American popular theater, Boucicault was on a crusade against this brand of what Dr. Eoin McKiernan would dub “shamroguery” a century later. Stephen Watt quotes Boucicault as saying:

The fire and energy that consists of dancing around the stage in an expletive manner, and indulging in ridiculous capers and extravagances of language and gesture, form the materials for a clowning character, known as the ‘Stage Irishman,’ which it has been my vocation to abolish.

Watt Stephen. 1991. Joyce, O’Casey and the Irish Popular Theater. 1st ed. Syracuse N.Y: Syracuse University Press.

Minnesota singer Michael Dean sang a few songs that reveled in stereotypes denigrating Irish immigrants alongside many other songs that preserved the dignity of his fellow Irish-Americans. His repertoire is a fascinating blend of older traditional songs and stage hits from his lifetime. He left only the above text for his version of this one so I have adapted it to a version of the usual melody as printed by Alfred Perceval Graves in The Irish Songbook.